The Supreme Court in Washington. (Alex Brandon/AP)

On Nov. 2, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in a case that literally could mean life or death for Blacks caught up in the United States’ judicial system, which highlights, again, the growing need for criminal justice reform.

In 1986, the Supreme Court ruled in Batson v. Kentucky that it is unconstitutional to dismiss a potential juror because of race. But the circumstances in Foster v. Chatman that are before the court demonstrate that such prosecutorial misconduct continue to persist, advocates claim.

“This is a practice we know is happening all over the country,” said Robert Dunham, executive director at the Death Penalty Information Center, “ is a symptom of something deeper that has been rooted in the judicial system.”

In fact, the phenomenon is indicative of the patriarchal—and racist—nature of the judicial system, in which those from the racial majority get to decide the fate of racial minorities, reform advocates say.

“The criminal courts are the part of the society that has been the least affected by the Civil Rights Movement,” said Stephen Bright, president and senior counsel of the Atlanta-based Southern Center for Human Rights. “Ninety percent of chief prosecutors are White and a number of decisions made are made by all-White juries. Even in communities with large populations of people of color, you will still have all-White juries deciding the fate of a Black youth—whether he lives or dies.”

And the pattern is particularly evident in cases involving Black defendants and White victims—cases that too often end in guilty verdicts. Since 1976, there have been 293 Black defendants executed for killing a White victim, while 31 White defendants have been executed for killing a Black victim, according to statistics from the Death Penalty Information Center.

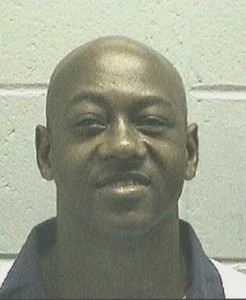

Timothy Foster (Courtesy Photo)

“Because prosecutors are overwhelmingly White, they tend to seek the death penalty for victims who are White. And if you add in defendants that are African-American those are the most highly-charged cases,” Bright said.

Such was the case for Timothy Foster, an intellectually-limited, 18-year-old, who lived in the projects in Rome, Georgia In 1987. The Black teenager was accused of killing former schoolteacher Queen Madge White, who was White. Prosecutors struck all four Black jurors out of the 42 persons qualified to serve on the jury. They also urged jurors to give Foster a death sentence to “deter other people out there in the projects,” according to the lawsuit.

During trial and on direct appeal, defense lawyers claimed race discrimination was evident in the selection of all-White jury, but the Georgia courts denied those claims. Nineteen years later, through an open records request, Foster’s lawyers obtained the prosecutors’ notes, which showed they were “somewhat obsessed with race,” Bright, Foster’s attorney, said.

The name of each potential Black juror was highlighted in the four-page jury list, the word “black” was circled on questionnaires for the prospective jurors and some of the prospective Black jurors were ranked, “B#1,” “B#2,” and “B#3,” in case “it comes down to having to pick one of the black jurors.”

The prosecutors then offered specious reasons for striking all the Black jurors from the pool, Bright added.

“Race affected the fact that the death penalty was sought in this case; race actively informed the exclusion of Black people from the jury and was a major factor in Foster being convicted,” he said.

Unlike other cases, the Georgia prosecutor’s notes were a “smoking gun” in terms of proving discrimination, Dunham added.

“The evidence is striking and graphic,” he told the AFRO. “You can see the evidence of race-consciousness and what you can also see is that the explanations the prosecutor offered to the court—explanations that are contradicted by his notes—show he was affirmatively trying to misrepresent what his reasons were for striking these jurors.”

Georgia’s court of appeals denied Foster’s claims, accepting the state’s argument that the prosecutors’ notes were not evidence of discrimination and that they had race-neutral grounds for challenging prospective Black jurors.

The AFRO reached out to the Georgia Office of the Attorney General for comment but did not receive a reply by deadline.